Title Photo by Benjamin Lehman on benjaminlehman.com

One of my favorite things to do when the weather is nice is go camping with my family. We swim, hike, and play all day, then at night, we sit around the campfire roasting marshmallows. One of my least favorite things about camping is when the wind blows the smoke from the campfire towards me, and I get a face full of dark grey air. It stings my eyes, and when I breathe, it burns. Luckily, all I need to do to make that better is to move further away from the fire. A little distance means I’m back breathing clean air.

But when I’m camping, that fire is pretty tiny and only putting out a little bit of smoke. I can move a few feet away and not have to worry about it anymore. But what if the fire was larger? If a fire is big enough, can I still feel the effects from far away?

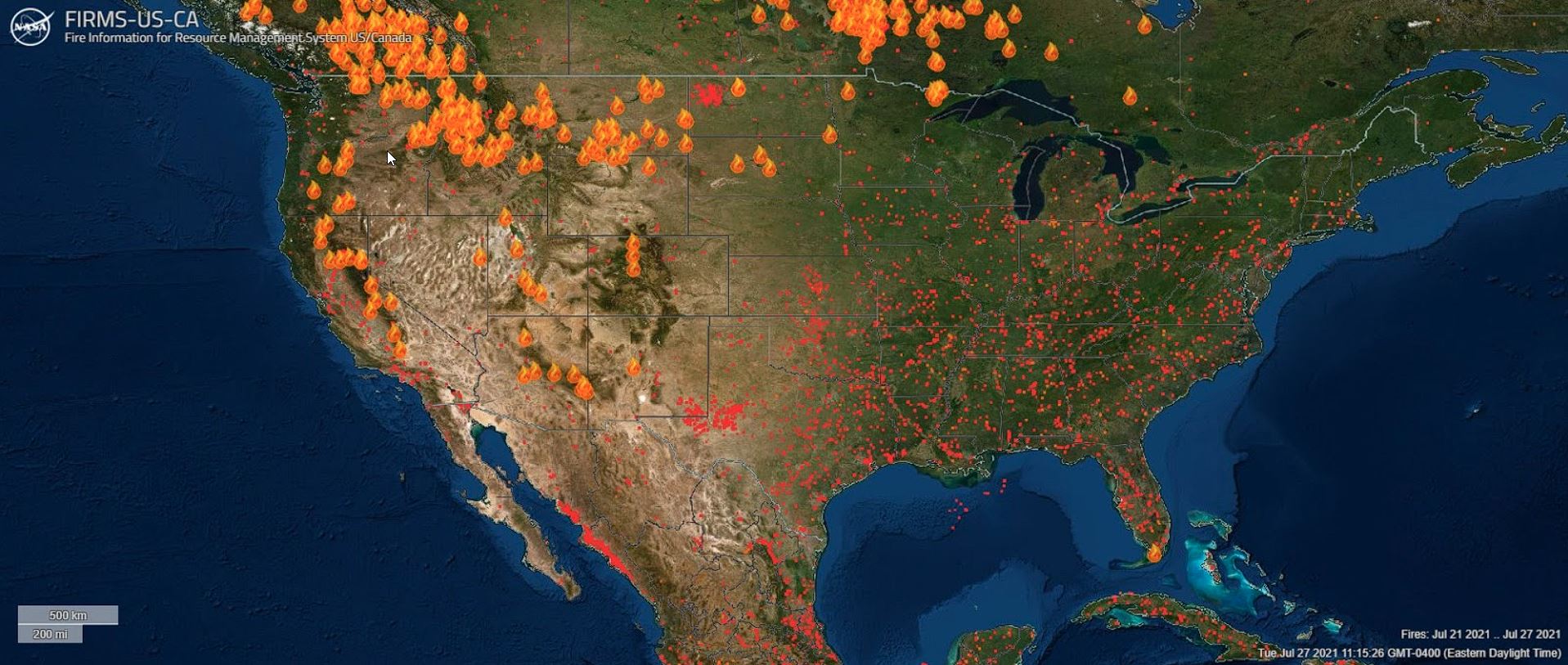

Recently there were some very large fires out in the Western United States, burning hundreds of square miles of trees, grass, and debris. Within a few days, smoke from those fires could be seen over New York City and Boston, over a thousand miles away! The below map from NASA and the US Forest Service shows just how widespread those fires were on July 27th.

Why it matters

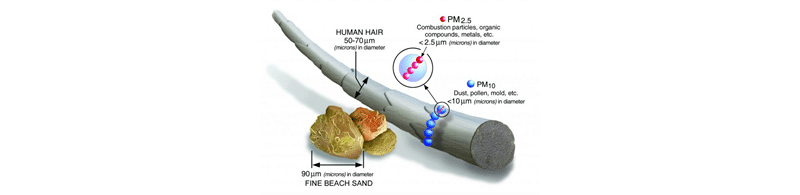

Smoke is made up of countless microscopic particles and gases, an important fact in understanding the effects of fires so far away. Those particles are why we can see the smoke and are known as particulate matter. With the right tools, like an air quality sensor, we can measure and count these particles.

The Environmental Protection Agency says that particulate matter measuring 2.5 micrometers, or about 30 times smaller than the width of a human hair, is small enough to breathe in and causes damage to our lungs and bodies. Smoke is full of particles that size, which is why we cough when a campfire blows in our faces.

Normally, a small amount of PM2.5 in the air is fine, but when there’s too much, it’s time to be concerned.

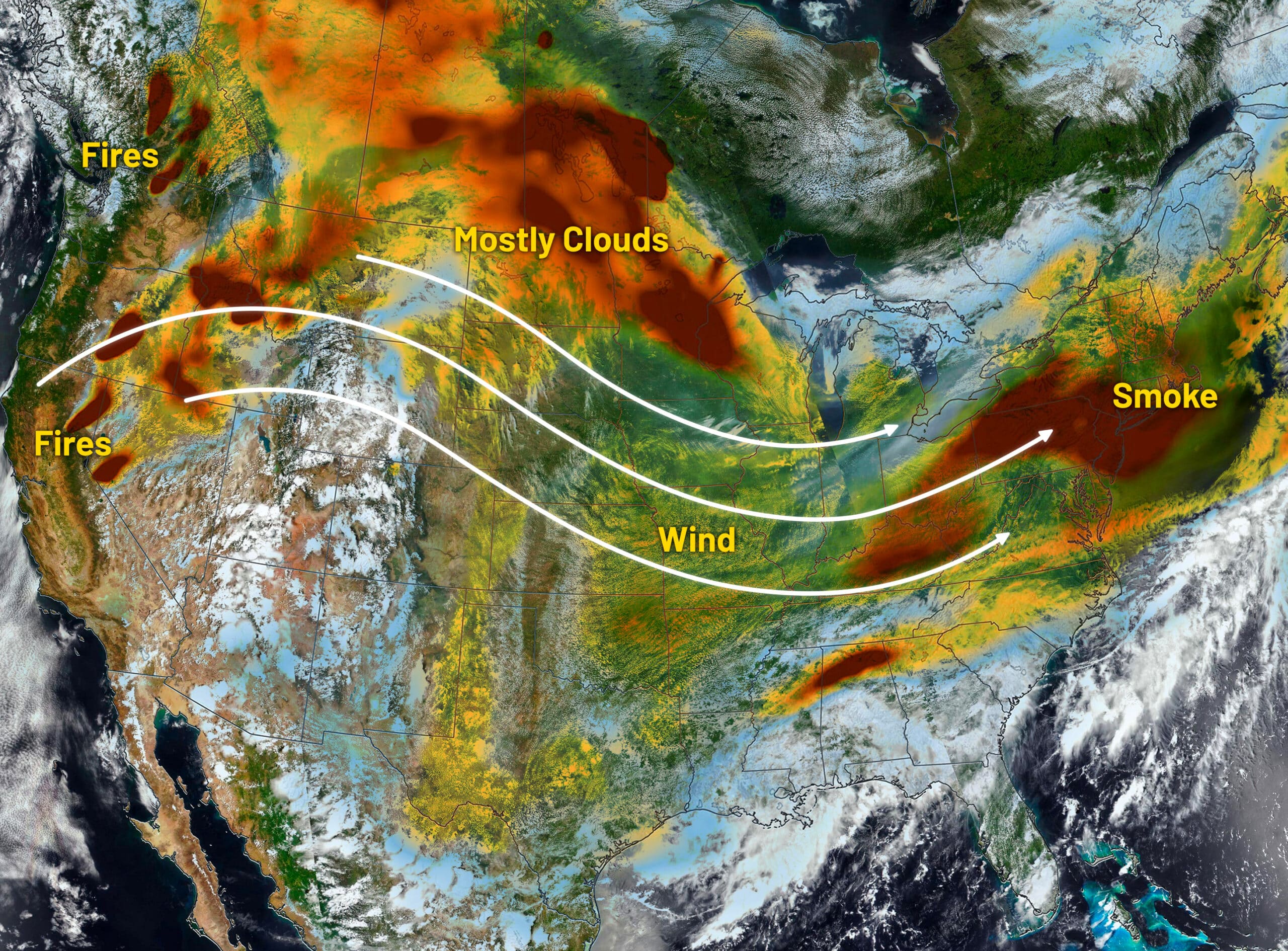

What Western Fires Mean for the East Coast

The satellite image above was taken on July 20th, when the fires out West were still burning hot. You can see the winds carried the smoke over to the East Coast, covering parts of New York and Massachusetts. For people in Boston that day, including many of the Blues team, the smoke was thick enough in the air they could see it.

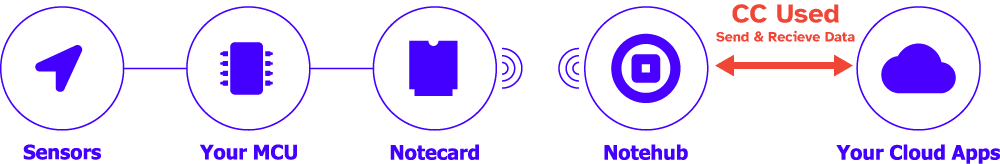

Luckily, a citizen scientist nearby had an Airnote air quality sensor from Blues Wireless actively recording data that we can see, including measurements of fine particulate matter. Thanks to the air quality data that the device sent back, we can see just how much was in the air before and after the smoke arrived.

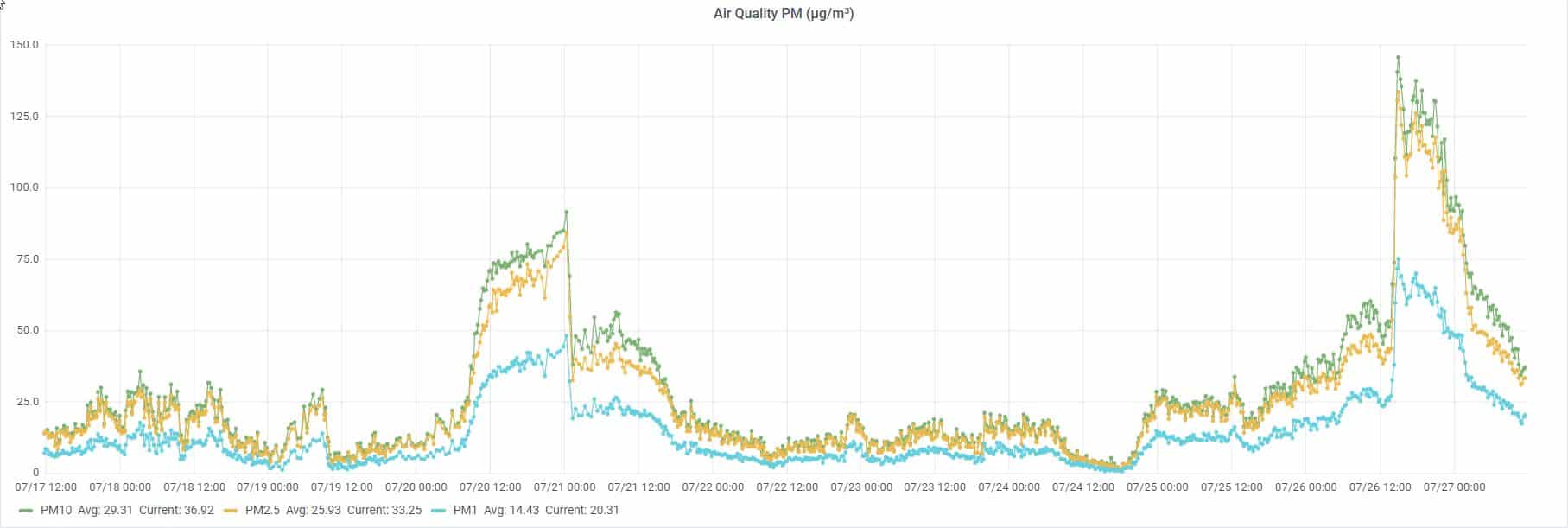

The graph of the data for the fine particulate matter shows that on July 20th number of fine particles rose by a large amount. In fact, it exceeded 50 µg/m3 (micrograms per cubic meter). Above this level Air Quality researchers on Airnow say things start to get concerning for sensitive individuals with asthma or breathing problems.

Unfortunately, that wasn’t the end of the large amounts of fine particles the Airnote caught during that time. On July 26 the count jumped to 133 µg/m3, a level Airnow designated as red level, or unhealthy for sensitive groups, and only 28 µg/m3 away from being unhealthy for everyone.

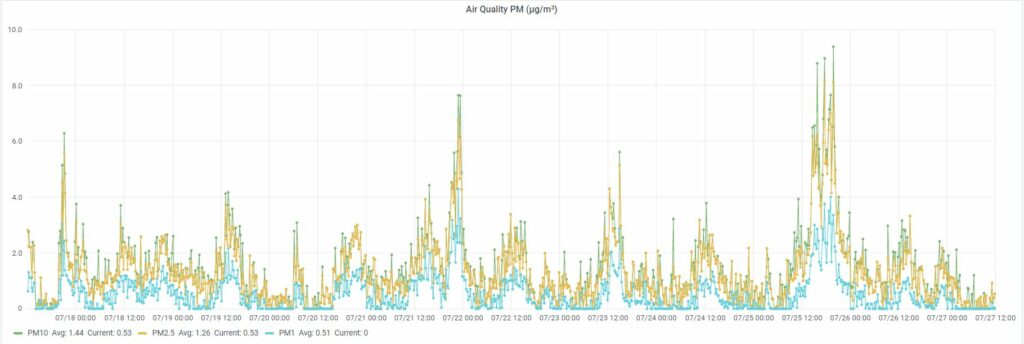

Just for comparison, in the below graph you’ll note an Airnote in Washington was located much closer to the fires, upwind and away from smoke, over the same time period saw a peak of 8.14 µg/m3, almost 16 times less than Boston’s high of 133 µg/m3.

This makes plain that you don’t need to be close to these large wildfires to see and feel the effects of the smoke. If you are watching an air quality sensor in your area and see the counts start to rise, check out your local news and see if planning for indoor activities is a good idea until the wind can move those fine particles out.